NO.70 GEORGE BRYDGES RODNEY of OLD ALRESFORD

Admiral of the Leewards

The bi-centennial of the death of

Lord Rodney falls in May 1992.

The bi-centennial of the death of

Lord Rodney falls in May 1992.

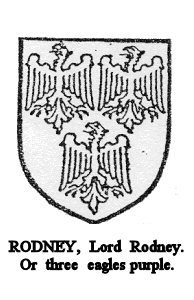

George Rodney came of an ancient family. Sir Richard Rodney fought beside Richard the Lion-heart at Acre. But long before that the family had been settled at Stoke Rodney in Somerset and for five hundred years the estates were handed down in unbroken succession. Rodney's father did not inherit then?: they passed through an elder branch into the Brydges family. George was born in 1719 and his father died in debt in the West country, George was brought up from early infancy by his godfather, George Brydges of Avington Park. Thus Rodney's introduction to the locality came at the very beginning of his life.

George was educated at Harrow, but at twelve years of age went to sea as a King^s Letter Boy. He was the last officer to enter the Navy in this way, as Lord Torrington was in the process of forming a Naval College at Portsmouth. At twenty Rodney received a commission just as the War of the Austrian Succession broke out. He served under Admirals Matthews and Vernon: then under Hawke he took part in the Battle of Finisterre in 1747. Now in command of the 60 gun Eagle Rodney received first £8,165 and in a later action £5,000 in prize money for enemy ships captured.

Now that he had some money of his own Rodney started the building of Alresford House on land which he had purchased near Old Alresford church. In this he was helped by his godfather: his banker was Mr. Magnus. In 1748 he bought further land which included Lanham and Pinglestone Farms and Gooseland Meadow. Alresford House took several years to complete. The contractor was Mr. Atkinson of Alresford and the architect was a Mr. Jones. Rodney paid a 'Mr. Chear' (later identified as Sir John Cheere) £300 for a carved chimney piece.

After his exploits at sea Rodney, introduced by Lord Anson,found favour with King George II and was popular at Court. In appearance he was an aristocrat with a thin masterful nose and a sharp chin. He was a dandy and very fastidious. Moreover he was a first class swordsman.

Rodney was appointed Governor of Newfoundland in 1749 and Mr. Brydges, his godfather watched over his interests in his absence. Before the house was completed George Brydges died whilst attempting to save one of his dogs from drowning in the river Itchen and the Avington Park estate went to the Duke of Chandos. All Mr. Brydges' other estates in the Alresford area were left in trust to his widow, to go after her death to Captain Rodney and his heirs: and failing them, to James his brother. This will was to cause a family quarrel and bring George much unhappiness.

After returning from Newfoundland Rodney, in 1753, married Jane Compton, sister of the Earl of Northampton. They lived happily for four years in a rare period of peace at Alresford House. Two sons were born: George, who became the second Lord Rodney and Jemmy, who as a naval commander was lost at sea in 1776. Among the Rodney papers about sixty letters have been preserved, which in the fashion of the time the couple wrote to each other even when together. They reveal mutual devotion of a high degree between two people who were wrapped up in their private lives, their children and their home- In one letter, to justify the expense of buying Old Alresford Pond, George wrote to Jane: 'the sale of the reeds (for thatching) only will pay me the interest on the money, and I may never again have such an opportunity of showing our mercy in not suffering the poor birds to be shot at -not to mention the opportunity of always having what fish we please'.

The Seven Years War broke out in 1755 and Rodney was recalled for service. This also marked virtually the end of their life together. In 1757 after the birth of a third child, Jane died at the age of 27 and was buried in St. Paul's. An. old family friend and several aunts looked after the children, whilst George placed a large and rather flamboyant memorial to Jane in Old Alresford Church. During the Seven Years' War Rodney served under both Hawke and Boscawen. In 1759. when British arms were triumphant in Canada and India, Rodney added to the record by destroying the flat bottomed boats of the Invasion Scheme at Le Havre and as a result was made a Rear Admiral at the age of 40. In 1761 he was appointed to the West Indies Station - 'The Station for .Honour', as Nelson put it later.

When he arrived at the station he set up headquarters in Antigua, One of the two main French islands, Guadaloupe, had been captured so the other, Martinique, was obviously the next point of attack. Martinque was thought to be impregnable. Rodney took personal charge of the combined operations. He landed the soldiers by a trick but they could not climb the fortified hills which surrounded Fort Royal, the capital. The officer In charge of the soldiers said he would need batteries drawn by mountain goats, When Rodney heard this, he sent his blue jackets ashore. There is in existence an eye-witness account of the action which followed ;

'You may fancy you know the spirit of these fellows: but to see them -in action exceeds any -idea that can be fawned of 'them. A hundred or two of them, with scopes and pulleys, will do more than all your dray horses in London. Let but their tackle hold, and they will draw you a cannon or mortar on its proper carriage up to any height, though its weight be never so great. It is droll enough to see them tugging along with a good 24~pounder at their heels. On they go, huzzaing and hallooing, sometimes uphill, sometimes downhill; now sticking fast in the brakes, presently floundering in the mud and mire: as careless of everything but the matter committed to their charge as if death or danger had nothing to do with them. They won the unbounding admiration of the soldiers, who vied with them in friendly fashion and brought their task to a triumphant conclusion'.

For this success Rodney was created a baronet. Before he reached Old Alresford again the peace had been signed and under the terms of the treaty both Guadaloupe and Martinique had been returned to France.

After his return to Alresford House Rodney married for the second time, in 1764, a lady of Dutch descent - Henrietta Clies, daughter of John Clies who spent most of his time in Lisbon as 'a man of business 1 . Rodney found everyone at home immersed in politics. He decided to join in, and thus keep himself under the eyes of the ministers and the Court. He was getting into debt and naval officers without a commission in peace time automatically went on half pay. Although not a true politician, he contested the seat of Northampton and won it at a personal cost, of £30,000. He had been appointed Governor of Greenwich Hospital and this, combined with being a Member of Parliament, kept him away from Alresford for months at a time. He continued to take a keen interest in his estates, and when his brother-in-law, the Earl of Northampton, employed Capability Brown to improve the grounds at Castle Ashby, Rodney was most annoyed to find that he himself could not afford to employ Brown. The enormous election expenses, plus his unemployed half pay, got him heavily into debt. These worries made him seriously ill and doctors were summoned from Bath to attend him at Alresford House. At one time he was actually in danger of arrest for debt. Under the will of George Brydges, mentioned earlier, Rodney had expected a substantial fortune. Before her death Mrs. Brydges had contrived to leave a large part of the estate to Rodney's brother James, her favourite. James built Upton House, just up the road from Alresford House with the bequest, on land which George considered should have justly been his. It is said that in the 17SOs George and his family planted a beech wood (there is one there to this day) to hide the sight of Upton House which they thought should have been rightly theirs.

In 1771 Rodney took the whole family with him on his appointment as Governor and Commander-in-Chief, Jamaica, This eased the financial burden quite considerably. However, on his return and still heavily in debt he decided to leave England for voluntary exile in order to avoid his creditors and went to live in Paris for some years. Whilst there he let Alresford House to a man called Bryan Edwards for £170 per annum.

When in 1778 France decided to take part

in the revolt of the American colonists

it would have been difficult to predict

that the English Admiral living in Paris

could have any part to play in this conflict.

He was entering his early sixties, gouty

and infirm. He was a prisoner riot of politics,

but because he had run up a fresh burden

of debts and could /not, with honour, leave

Paris until they were paid off. Early in

1778 he wrote to Lord Sandwich, the First

Lord of the Admiralty, offering his services

across the Atlantic and mentioning in passing

his friendship with King George III, who

was very fond of him. Sandwich ignored

this and Rodney was hurt; he wondered how

he could get back to England without money.

Lady Rodney went to London to seek help

from friends. Here she had no success,

but cheered up when she had a letter from

her husband saying that an old friend,

the Marshal de Biron, had offered him enough

money (1,000 louis) to pay off his creditors.

Twice Rodney refused, but because he was

so anxious to render service by getting

back to England he accepted when asked

for the third time.

When in 1778 France decided to take part

in the revolt of the American colonists

it would have been difficult to predict

that the English Admiral living in Paris

could have any part to play in this conflict.

He was entering his early sixties, gouty

and infirm. He was a prisoner riot of politics,

but because he had run up a fresh burden

of debts and could /not, with honour, leave

Paris until they were paid off. Early in

1778 he wrote to Lord Sandwich, the First

Lord of the Admiralty, offering his services

across the Atlantic and mentioning in passing

his friendship with King George III, who

was very fond of him. Sandwich ignored

this and Rodney was hurt; he wondered how

he could get back to England without money.

Lady Rodney went to London to seek help

from friends. Here she had no success,

but cheered up when she had a letter from

her husband saying that an old friend,

the Marshal de Biron, had offered him enough

money (1,000 louis) to pay off his creditors.

Twice Rodney refused, but because he was

so anxious to render service by getting

back to England he accepted when asked

for the third time.

Having paid off his debts both in France and England Rodney decided to jog Sandwich's memory with regard to the conduct of fleet operations during the revolt of the American colonists and the aggressive posture of the French fleet on what was now called the Leeward Islands Station, He wrote a remarkable essay which he called His Memorandum. In this he pointed out that the duties of the fleet on the other side of the Atlantic were twofold. It was needed to carry out operations off the coast of New England together with protection of the British possessions in the West Indies. These two tasks required a considerable force: Rodney showed how the numbers of ships needed could be. reduced. Off North America the weather required the withdrawal of ships to winter quarters after October. But in the West Indies the hurricane season ended in the same month. The same ships could be used from October to May in the West Indies and from May to October off North America. Lord Sandwich was sympathetic: but Rodney had been too long away in France. All the appointments had been made. The Honourable Samuel Harrington had already left to take command of the Leeward Islands Station. So George had missed his chance. He talked to the Whigs. He talked to the Tories, He talked to anyone who might get-him out to the West Indies, Then he obtained the King's sympathy by criticising the Whigs. After eighteen months he got his chance. Harrington, in a brilliant series of operations, had captured St. Lucia again from the French but had been badly wounded and had to return home. Rodney accepted command of The Leewards in his place.

Rodney took up his command at a most unhappy

time. The American John Paul Jones had

been causing havoc amongst English shipping

in the Channel. Spain had come into the

war and the English garrisons at Gibraltar

and Minorca were being blockaded. Rodney

was sent to the West Indies by way of the

besieged garrisons with, orders to take

supplies and destroy or capture as many

enemy ships as possible. In spite of the

delay caused by atrocious weather Rodney,

flying his flag in the 90 gun Sandwich,set off

in 1780 and on 7th January spotted

22 sail and captured the lot. Ten days

later he defeated the Spaniards in the

famous Moonlight Battle, which went on,

most unusually for the period, until 2

a.m. by moonlight, destroying or making

prizes of the enemy ships and then relieving

the garrisons.

Rodney took up his command at a most unhappy

time. The American John Paul Jones had

been causing havoc amongst English shipping

in the Channel. Spain had come into the

war and the English garrisons at Gibraltar

and Minorca were being blockaded. Rodney

was sent to the West Indies by way of the

besieged garrisons with, orders to take

supplies and destroy or capture as many

enemy ships as possible. In spite of the

delay caused by atrocious weather Rodney,

flying his flag in the 90 gun Sandwich,set off

in 1780 and on 7th January spotted

22 sail and captured the lot. Ten days

later he defeated the Spaniards in the

famous Moonlight Battle, which went on,

most unusually for the period, until 2

a.m. by moonlight, destroying or making

prizes of the enemy ships and then relieving

the garrisons.

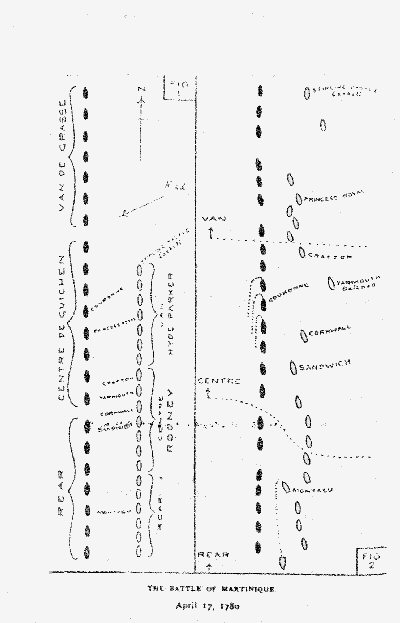

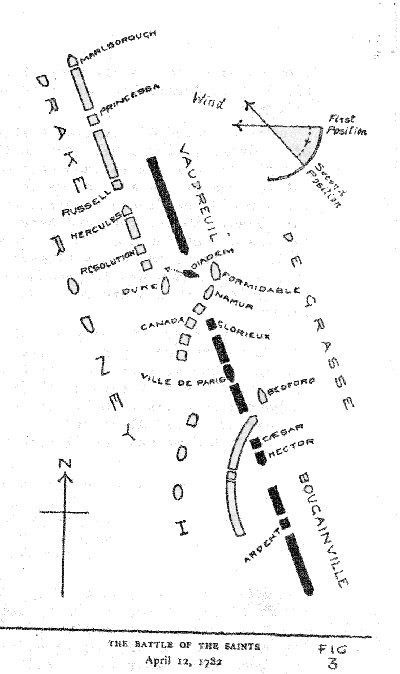

Rodney appeared in the West Indies in April. At the Battle of Martinique (see Figs. 1 and 2) he defeated the French Admiral de Guichen by using new tactics of> concentration of fire on selected enemy ships . This was heresy to the Board of Admiralty, as the accepted procedure for centuries had been to get. into a parallel line with one's enemy: ships opposite each other hammered away at close range until one or the other was disabled or sunk. Rodney was to use these unorthodox —- tactics again two years later at the Battle of the Saintes (Fig, 3}, when he directed his divisions to cut through the enemy line. These ideas established Rodney as one of our foremost Admirals, in the writer's opinion second only to Nelson, who was to use these selfsame tactics at Copenhagen and Trafalgar.

When the news of the Battle of Martinique reached England Rodney was granted a pension of £2,000 a year. Even de Guichen, now disgraced sent him a message of congratulations.

Rodney went on to capture the small Dutch trading island of St. Eustatius without a shot being fired, collecting 130 merchantmen and £3,000,000 in plunder. He was awarded the Order of the Bath in his absence. Eventually his health broke down, he was relieved by Admiral Hood and he returned to England for treatment. At home he was extremely popular and his friendship with the King continued; however he was constantly and viciously attacked by Edmund Burke in and out of Parliament, who accused him of 'gloating over his moneybags'. Burke had no particular enmity for Rodney: his main target was the establishment.

Admiral de Grasse had replaced de Guichen and was engaged in recapturing the West Indian Islands one by one, which Hood was unable to prevent. Finally, the French by blockading Chesapeake Bay hastened the surrender of Cornwall is at Yorktown and the loss of the American colonies. When the news was received at home King George III, without consulting anybody, asked Rodney to go and save the West Indies from the French. Rodney, aged 64, stricken with gout, barely recovered from an operation, arrived off Barbados 'with his squadron and flying his flag in Formidable, after taking only five weeks to cross the Atlantic!

He collected all available ships and waited at St. Lucia for news of de Grasse, flying his flag in the Ville de Paris. He caught up with him off the Saintes Islands near Guadeloupe on 12th April 1782. This battle, one of the roost decisive in naval history, ensured that never again would the French maintain any large scale presence in the Caribbean. Rodney returned home, as a conquering hero using his tactics of cutting through the enemy line, he had actually captured Ville de Paris, the enemy flagship! (Fig.3). Landing at Bristol, his journey to London was in the nature of a triumphant progress. Reaching the capital, he was created a Baron and awarded another pension of £2,000.

Rodney lived for ten years after the Battle of. the Saintes. He stayed for the most part at Alresford. Our last glimpse of him is at Alresford House, surrounded by his children and grandchildren and writing to his secretary on their behalf for lottery tickets. He died in London on a visit: to his son on 24th May 1792, and seven days later vas buried in Old Alresford Church. The monument to his memory in St. Paul's Cathedral was the first erected there.

Copyright John Adams July 1991

Sources -The Rodney Papers HRO

Sea Kings of Britain Geoffrey Callender 1930

George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron Peter Davies Rodney David Han nay 1891

The Seafarers - Fighting Sail Time Life Books

Anecdote. The story is told of a. one legged veteran a patient in the Edinburgh Infirmary, who being ask&d by Dr. John Barclay ''Where did you lose your leg, my man?' briefly replied 'At the 12th April, your honour'* The doctor, not immediately calling to mind the great day, enquired again 'What 12th April? ' Jack looked him in the face with supreme contempt and retorted indignantly 'WHAT 12th of April? Who never heard of any 12th April by ONE?',

H.M.S. Rodney. The writer likes to compare the career of this 16" gun battleship with the man after whom she was named. She carried out useful and profitable tasks during her youth, and middle age and in her old age played a large part in the sinking of the Bismark, as much a menace to Britain as the Ville De Paris had been a century and a. half before .