NAPOLEONIC PRISONERS OF WAR IN ALRESFORD

By

Peter Hoggarth

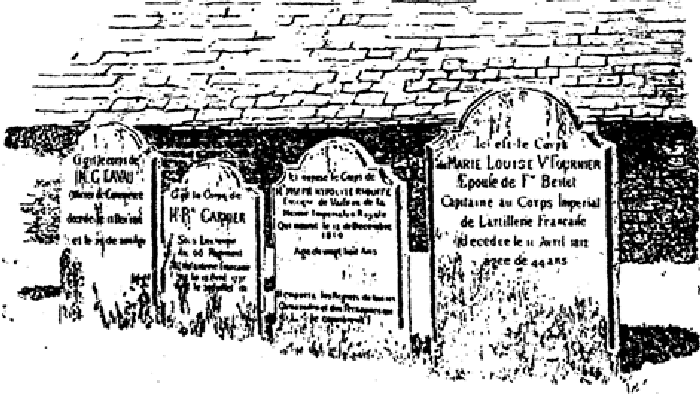

A visitor to the churchyard of St. John the Baptist church in Alresford may wonder why, near the west door of the church, there are five old French gravestones. They date from the Napoleonic Wars: four French officers and the wife of another officer are buried in the churchyard.

There are references to French prisoners in Alresford in earlier times. In 1705 the first Frenchman to die in captivity was buried here. Canon A.J. Robertson in his 'History of Alresford' records that in 1757 there were three hundred prisoners in Alresford, and from another source we learn that French prisoners helped extinguish a fire in a wood yard in 1736. Britain was at war with France, and sometimes Spain, through out much of the eighteenth century and Alresford was one of the towns where French and Spanish prisoners were held on parole.

We know most about the prisoners taken during the Napoleonic Wars. Between 1793 and 1815 over two hundred thousand prisoners of war were brought to Britain. They were mainly French but included citizens from countries at one time or another allied to or controlled by France, in particular Holland and Spain. The War of 1812 with the United States led to the capture of a number of Americans. Prisoners were held in hulks (prison ships) in land prisons or under guard in houses or other suitable buildings. Officers were offered parole and were required to give their word of honour in writing not to try to escape. An officer who broke his parole might be sent to the hulks, rightly regarded as a dreadful fate. Sometimes French officers were exchanged with British prisoners held in France, and wives and children in France might join officers in England. Alresford was one of eleven parole towns in Hampshire. Other parole towns included Andover, Bishops Waltham and Odiham.

I am much indebted to Audrey Deacon for her excellent book 'The Prisoner from Perrecy' which-gives background information upon the subject of prisoners of war in Alresford (and elsewhere) as well as an account of the life of Second Lieutenant Pierre Garnier, a French officer taken on the West Indian island of Guadeloupe in 1810, who lived on parole in Alresford, died and was buried here. His grave is one of the five in the churchyard.

Prisoners of war were the responsibility of the Transport Board of the Admiralty. On arriving in Alresford, often from Portchester Castle transit camp, each prisoner was given a copy of the conditions of parole printed in both French and English. This document had a physical descr iption of the prisoner and was in effect an identity card. It stated that the prisoner was allowed to walk on the 'Great Turnpike Road' (a continuation of East Street) not more than a mile from the town limits; that he must not go into any field or cross road and must not be out of his lodgings between certain hours - in effect after dark. The householder upon whom the prisoner was billeted was given a printed reminder of his responsibility to see that the prisoner obeyed these instructions. Notices were displayed prominently in Alresford drawing attention to the restrictions imposed upon the prisoners and offering rewards to residents reporting any infringements.

The prisoner was required to report to the Transport Board's local agent twice a week from whom he drew his allowance of 1s6d per day, the rate for Second Lieutenants and above. John Dunn, the agent, was an Alresford solicitor with a house and office in East Street. He was responsible for billeting prisoners with suitable families, dealing with complaints, and for ensuring that all correspondence was transmitted through the Transport Office. Censorship of correspondence was required for security reasons, rather necessary when we learn that on the 23rd June 1811 three officers escaped from Alresford! Nothing is known of the fate of these escapees. 'John Dunn supervised conduct and reported escapes and attempted escapes, and each month he submitted accounts which were closely examined by the Transport Board.

A surgeon was available if a prisoner

was taken ill. When a death occurred

the agent took possession of the deceased's

personal property, sent an inventory

to the Transport Board and arranged for

the funeral and the sale of effects.

The Transport Board would later transmit

the money to the next of kin or to the

legal representative.

A surgeon was available if a prisoner

was taken ill. When a death occurred

the agent took possession of the deceased's

personal property, sent an inventory

to the Transport Board and arranged for

the funeral and the sale of effects.

The Transport Board would later transmit

the money to the next of kin or to the

legal representative.

The allowance of 1s6d per day covered food, clothing and lodging, and was often found to be inadequate. To eke out the allowance several officers might feed together in a mess. We know from accounts of life in other Hampshire towns that Frenchmen sometimes searched hedgerows for snails, much to the surprise of the locals. Extra funds were essential and one way to obtain them was for the Frenchman to give lessons in French, drawing and fencing. They also made articles for sale in the local market.

The most enduring monuments to these Frenchmen were the model ships which they fashioned. The raw material consisted of meat bone bleached by long boiling and polishing and shaping. Wood was also used. The shaping of the bones appears to have been done with sharp needles and gouges. The rigging was made by plaiting hair. A high level of practical knowledge and skill was demonstrated. There are two fine models of British warships in the Maritime Museum in Southampton. They are very large, one being well over a yard long and more than two feet high.

These models did not originate in Alresford but were made elsewhere, probably at Portchester from where most models came. However some model ships were undoubtedly made in Alresford, where the local French men were sufficiently skilled to make tobacco boxes, sets of dominoes and bobbins for use in the making of lace. Other Alresford relics of the period include an ornamental brass ring with 'Calais' on one side and a drawing of a ship on the other, and a French gold coin found in an attic in Broad Street.

Something must now be said of the life of 'The Prisoner from Perrecy'. Pierre Garnier was born in 1775 in Perrecy in Burgundy. He enlisted in the 66th Infantry Regiment in 1796, sailed to Guadeloupe in 1810 and was captured in that year in the course of a British attack on the island. Gamier arrived at Portchester Castle in June and was discharged to Alresford the same month. In 1811 he was taken ill, possibly as a result of the debilitating conditions endured in the West Indies. In June 1811 he prepared a claim for arrears of half pay to which he was entitled as a prisoner but the claim was not settled (on behalf of his heirs) until six years after the end of the war. Garnier died on 31st July 1811. It seems that Gamier's heirs were more fort unate than the British Government which had hoped to recoup the cost of supporting French prisoners in Britain from the French Government, but in fact received nothing.

French prisoners gravestones

History of Alresford - A J Robertson

Although the combined French and Spanish fleets were largely destroyed at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 the possibility of invasion was still taken seriously. In 1810 the threat was regarded as sufficiently serious for many prisoners to be transferred from the vulnerable south of England to Scotland. Napoleon abdicated in 1814 and was finally defeated at Waterloo in 1815 and all prisoners were soon repatriated.

In December 1959 the five French gravestones in the churchyard were cleaned, relettered and weather proofed, the cost being borne by the French Military War Graves Commission. In February 1960 there was a moving ceremony attended by the Rector, the Rev; A.J. Pearson M.C., and representatives of the British Legion and the Parish Council, when Mon. C.L.R. Fillias the French Vice Consul at Southampton placed a floral wreath draped with the Tricolour on the graves.

To conclude this narrative on a more cheerful note, it appears that the French prisoners (referred to locally as the 'Frenchies')were well treated in Alresford and were quite popular with the local inhabitants. Indeed there was some mixing with Alresford families. One amusing episode occurred in 1810 when an Anglo-French assembly was arranged at The Swan to celebrate the marriage of Napoleon to Marie-Louise of Austria. John Dunn and various Alresford notables were to attend, however the Transport Board heard of the affair and forbade the celebrations to take place. It is astonishing that Alresfordians were preparing to celebrate the marriage of their country's arch enemy! In 1811 the Transport Board wrote to John Dunn stating that they understood that the French officers had formed a theatre and warning that if the theatre continued the prisoners would be moved elsewhere. It seems that the good people of Alresford were more compassionate than the Transport Board.

Copyright Peter Hoggarth November 1990

Sources Hampshire Record Office

Southern Evening Echo

Paul Chamberlain - Records and Research Laurence Oxley - Manuscript 1970

Audrey Deacon - The Prisoner from Perrecy

Dominoes carved from bone by French officers - Ursula Oxley from the Laurence. Oxley Collection